Wabi-Sabi (侘寂): The Profound Art of Finding Beauty in Life's Beautiful Brokenness

Why Your Flaws Are Your Superpower

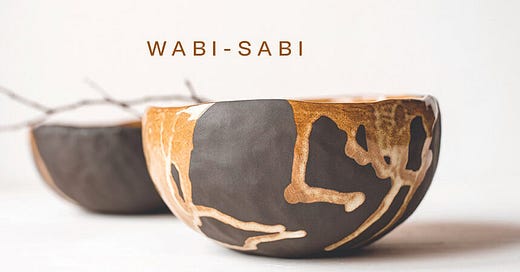

In the 16th century, Japanese tea master Sen no Rikyū deliberately chose rough, asymmetrical tea bowls over pristine porcelain for his ceremonies. He understood something we've forgotten: perfection is sterile, but imperfection is alive.

In our hyper-curated world of filtered selfies and algorithmic perfection, we've lost touch with a fundamental truth that has guided Japanese culture for over 400 years. Wabi-sabi (侘寂) literally "rustic simplicity" and "elegant imperfection" isn't just an aesthetic philosophy. It's a radical act of rebellion against our culture's exhausting pursuit of flawlessness.

The Hidden Cost of Our Perfection Obsession

Consider this: the average person checks their phone 96 times daily, often comparing their behind-the-scenes reality to others' highlight reels. We spend billions on products promising to "fix" us, from anti-aging creams to productivity apps that pledge to optimize every moment. Yet rates of anxiety and depression continue climbing, particularly among young people drowning in perfectionist expectations.

What if the problem isn't that we're broken, but that we've forgotten how to see beauty in our brokenness?

Understanding Wabi-Sabi: Beyond the Surface

Wabi-sabi (侘寂) emerges from three Buddhist principles that challenge Western thinking:

Mono no aware (物の哀れ) - The bittersweet awareness of impermanence

Wabi (侘) - Finding beauty in rustic simplicity and humble imperfection

Sabi (寂) - Appreciating the patina of age and the wisdom of weathering

This isn't about settling for mediocrity or abandoning excellence. It's about recognizing that true beauty often lies in the spaces between perfection in the asymmetry, the wear, the gentle decay that tells the story of a life fully lived.

The Neuroscience of Imperfection

Recent research reveals something remarkable: our brains are actually wired to find imperfection more engaging than perfection. Dr. Anjan Chatterjee's studies at the University of Pennsylvania show that we pay more attention to slightly asymmetrical faces and find them more memorable than symmetrical ones. Perfect symmetry, it turns out, signals artificiality to our ancient neural networks.

This explains why a handmade ceramic bowl, with its subtle irregularities and finger impressions, feels more alive than machine-manufactured perfection. Your brain recognizes the human touch the beautiful evidence of someone's presence in the making.

The Relationship Revolution: Love in the Age of Imperfection

Harvard's Grant Study, following subjects for over 80 years, reveals that the happiest people aren't those with perfect relationships, they're those who've learned to love imperfectly and be loved in return.

Real intimacy happens in the spaces between perfection: when you laugh together at a cooking disaster, when you comfort each other through failures, when you choose to stay despite seeing each other's flaws clearly. As poet Adrienne Rich wrote, "There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep and still be counted as warriors."

The Japanese have a word for this too: kintsugi relationships bonds that become more beautiful at the broken places, strengthened by shared vulnerability rather than mutual performance.

Wabi-Sabi as Resistance

In a culture that profits from our insecurities, embracing wabi-sabi is revolutionary. It means:

Posting the unfiltered photo

Serving the lopsided cake with joy

Wearing the vintage dress with its small stains

Keeping the books with their cracked spines

Loving your aging face in the morning light

Each of these acts declares: "I am not a project to be perfected. I am a human being worthy of love exactly as I am."

The Science of Enough

Psychologist Tim Kasser's research shows that cultures emphasizing intrinsic values (relationships, personal growth, community) over extrinsic ones (wealth, image, fame) report higher levels of well-being. Wabi-sabi (侘寂) naturally guides us toward intrinsic values, helping us find satisfaction in what we already have rather than constantly seeking more.

This isn't about lowering standards, it's about changing the metrics entirely. Instead of measuring worth by flawlessness, we measure it by authenticity, resilience, and the depth of our connections.

A 30-Day Wabi-Sabi Challenge

Week 1: Notice

Spend 5 minutes daily noticing something imperfect that you find beautiful, cracked pavement where flowers grow, an elderly person's hands, shadows cast by uneven objects.

Week 2: Accept

Practice self-compassion when you make mistakes. Instead of harsh self-criticism, try: "This is what it means to be human. I am learning."

Week 3: Create

Make something imperfect on purpose, a crooked drawing, an off-key song, a meal that doesn't match any recipe. Share it with someone you love.

Week 4: Integrate

Choose one "imperfect" thing about yourself that you've been trying to fix. Practice seeing it as part of your unique beauty instead.

The Long View: Aging as Art

In Japan, the aesthetic of mono no aware—the pathos of things—teaches us that impermanence itself is what makes beauty poignant. Cherry blossoms are treasured not despite their brief bloom, but because of it. Their fleeting nature intensifies their beauty.

What if we applied this lens to our own aging? Instead of fighting the changes time brings, what if we saw them as our personal artwork in progress, each line a brushstroke, each grey hair a silver thread in our tapestry?

Finding Your Wabi-Sabi

The path to embracing imperfection isn't about becoming careless or abandoning growth. It's about recognizing that you are already whole, already worthy, already enough not despite your imperfections, but because of them.

Your quirks, your scars, your asymmetries, your growing edges, these aren't bugs in your system. They're features. They're what make you irreplaceably, beautifully you.

In the end, wabi-sabi offers us the most radical gift of all: permission to be human. To love our cracks because they let the light in. To find peace in the space between perfect and broken, where real life, messy, tender, and utterly magnificent actually happens.

The bowl that has been mended is more beautiful than the bowl that never broke.

Take a moment now to look around you. Find something imperfect and beautiful. Really see it. That's your first step into the profound practice of wabi-sabi (侘寂) the art of loving what is, as it is, right now.