Multiply by Zero: Why One Weak Link Cancels Everything

The mental model for finding and removing the single bottleneck killing your team's output

Why exceptional execution still fails and how to fix it.

In mathematics, multiplication by zero yields zero. Always.

5,000 × 873 × 42 × 0 = 0

Stare at that for a second. All those huge numbers, completely wasted. One zero kills everything.

You already know this feeling. Your talented team ships nothing. Your strategy dies in execution. You add resources, run more meetings, buy better tools… and velocity stays flat.

Here’s why: You’re playing addition when your system runs on multiplication.

Why Smart Systems Fail

We optimize what we can see: more training, more features, more tools. This is addition thinking. It misses the reality: most systems are multiplicative.

Your marketing × product quality × customer service × operational efficiency. One of these approaches zero, and the outcome is zero.

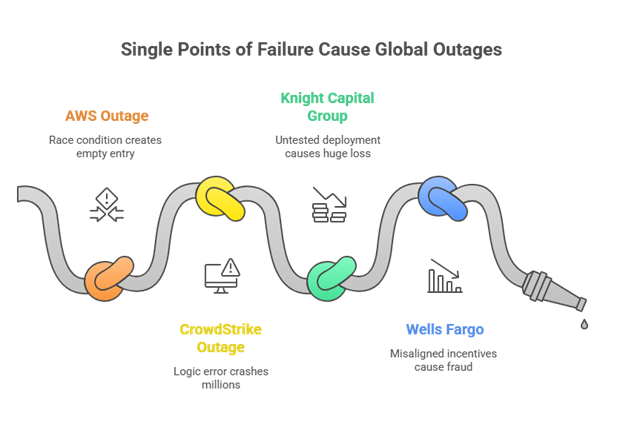

Examples:

AWS Outage (October 2025): A race condition, two systems trying to update the same DNS entry simultaneously, created an empty database entry. That single bug cascaded into global failures affecting Snapchat, McDonald’s, Disney, Coinbase, and millions of users. One synchronization error, hours of worldwide disruption.

CrowdStrike Outage (July 2024): A single logic error in one configuration update file crashed 8.5 million Windows systems globally. Airlines grounded flights. Hospitals canceled surgeries. Banks shut down. One faulty update, estimated $10 billion in damage worldwide.

Knight Capital Group (2012): $440M lost in 45 minutes due to one untested deployment. Expertise, infrastructure, years of experience, all wiped out by a single zero.

Wells Fargo (2016): Incentives misaligned. 3.5M fake accounts. One zero in alignment caused systemic fraud.

Pattern: The zero is rarely in what you measure, it’s usually what you avoid talking about.

Where Your Zeros Hide

Zeros don’t appear in dashboards. They hide in:

“That’s just how we do it here.”

Handoffs between teams that take four days.

Meetings where decisions go to die.

A single blocker everyone knows about but nobody has permission to fix.

Scrum example: Your standup says “no blockers,” yet a team has been waiting on an API spec for a week. That politeness? That’s your zero.

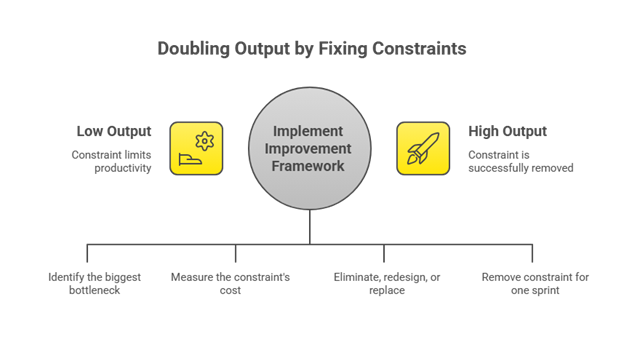

The Framework That Actually Works

Step 1: Name It

Ask: “What single thing, if fixed tomorrow, would double our output?”

First answer = your constraint. That’s your zero.

Step 2: Quantify It

Make it visceral. If deployment takes 2 days instead of 2 hours, and you deploy 20 times per sprint, you lose 38 hours per sprint, a full week of value gone.

Step 3: Choose Your Move

Eliminate: Does this need to exist?

Example: Daily status emails duplicating Jira. Stop for two weeks. If nobody asks, it was waste.Redesign: Keep what’s necessary, fix the process.

Example: Code reviews taking 3 days. Change from “async whenever” to pairing within 4 hours.Replace: Swap what can’t be fixed.

Example: Legacy deployment failing 30% of the time → modern CI/CD. Calculate ROI.

Step 4: Test Small

Remove the zero for one sprint. Measure the outcome. If velocity improves, make it permanent.

Why This Hits Different

Netflix didn’t optimize DVD delivery, they eliminated physical media when it approached zero value.

Spotify didn’t add processes, they removed cross-team dependencies that blocked autonomy.

Amazon simplified approvals with “two-way door” decisions, multiplying execution speed.

The math:

Addition thinking: 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 1 = 29

Multiplication reality: 7 × 7 × 7 × 7 × 1 = 2,401

Fix the constraint: 7 × 7 × 7 × 7 × 3 = 7,203

Fixing the weakest point creates exponential gains. One removal often beats adding three new tools.

What This Looks Like Monday Morning

Scenario: Sprint velocity plateaued despite adding a developer.

Map: Workflow from story selection → production.

Measure: 40% of sprint time blocked waiting for QA.

Test: “If we solved QA, what changes?” Development moves fast, validation slows.

Act: Pair developers and QA during development.

Result: Stories move 60% faster next sprint.

You didn’t add resources. You removed a zero.

The Uncomfortable Truth

You probably already know your zero. You’ve been working around it for months.

For ICs: unclear requirements, unrealistic deadlines, or a senior dev ghosting code reviews.

For managers: the approval bottleneck, overlong meetings, or a pet project going nowhere.

The blocker isn’t awareness, it’s permission to act.

The Core Question

In your current initiative: what single element, if it fails, makes everything else irrelevant?

That’s your zero.

Remove it, and everything you’ve built finally multiplies.

The Math Doesn’t Negotiate:

Zero × anything = zero.

The Leverage:

Remove one zero, and the talent, strategy, and effort you already invested can finally multiply.

Your move: This week’s retro, ask:

“What single change would double our output?”

The first uncomfortable silence? That’s your team realizing they already know the answer.

The CrowdStrike example perfectly illustrates your multiply-by-zero framework. What's fascinating is that CrowdStrike wasn't a failed company - they were a leader in cybersecurity. Their tech, their team, their processes were all strong (7s and 8s). But a single untested edge case in a config file update became the zero that crashed 8.5 million systems. This is what makes multiplicative systems so dangerous - you can't compensate for a zero by being stronger elsewhere. No amount of technical excellence in their detection algorithms could overcome that single deployment weakness. The real insight here is that organizations spend most resources optimizing their 7s into 8s (better features, more training, faster deplopyment), when the ROI is actually in finding and eliminating the hidden zeros. The zeros are usually in the boring stuff nobody wants to talk about - deployment testing, rollback mechanisms, canary processes. Those aren't exciting sprint goals, but they're the difference between world-class execution and $10B in damages. Your framework gives teams permission to stop adding and start removing, which is counterintuitive but mathematically correct.

The CrowdStrike example perfectly captures your multiply-by-zero thesis. What strikes me most is how the system appeared resilient right up until it wasn't - 8.5 million systems, thousands of expert IT teams, billions in redundancy spending... all canceled by one bad config file. The failure wasn't in the endpoint protection itself but in the assumtion that "tested code" meant "safe deployment."

Your framework (Name It → Quantify It → Choose Your Move → Test Small) would have caught this. If CrowdStrike had asked "what single thing, if it fails tomorrow, would cause catastrophic damage?" the answer would have been: our auto-update mechanism with insufficient canary testing. The zero was hiding in plain sight - the deployment process everyone trusted precisely because it had never failed before.

The AWS race condition is equally instructive. Two systems writing to the same DNS entry simultaneously seems like such an obvious zero in retrospect, but in complex distributed systems, these edge cases multiply faster than you can enumerate them. The real lesson: your zeros aren't where you're looking (the code) but where you've stopped looking (the handoffs, the assumptions, the "it's always worked this way" infrastructure).

One question though: in heavily regulated environments (healthcare, finance), the "remove for one sprint" test becomes harder - you can't just experiment with HIPAA compliance or payment processing. How would you adapt Step 4 when the zero is embedded in a compliance requirement that can't be temporarily removed?